This blog describes my efforts over the last couple of decades to set up and establish strong international collaborations, mostly in the Far East (Japan and China). Hopefully, those of you reading this will pick up some useful tips and if you are just starting out, you’ll see that the effort put in does eventually pay off. For those who gave up along the way, maybe this blog will persuade you to give it another go.

My first trip to the Far East was back in 1996 for the Hong Kong v England football match. Those of you who follow the game will remember this trip for the infamous ‘dentist’s chair’. My lasting memory was that this was an exciting part of the world and somewhere I would want to visit much more often. My initial scientific interactions with the Far East came a few years later (1999), when I was a lecturer at UEA and we had a visit from Prof. Takehiko Yamato of Saga University in Japan. He was an organic chemist with much experience of calixarene chemistry, and this was a perfect match for the metal chemistry I had been doing for some time with related systems. UEA and Saga had signed an agreement, and were therefore very keen that people would travel in the opposite direction. In the early 2000s, I volunteered for a few such trips, and prior to travelling made sure that I browsed the recent literature and identified Japanese authors that might be interested in my work, e-mailed them and more often than not got invited to give a seminar. I could then arrange the itinerary well in advance, and back in 2002, I managed to give a seminar in each of the cities that England played a world cup game in the day before the game – this of course was sheer coincidence! Japan is not cheap and so it’s important to sort out some funding prior to deciding to visit for any length of time. Some lucky people will work in departments who are willing to support such trips particularly if the benefits can be clearly identified. For my early trips, one very useful source of travel funds was the RSCs Journals Grants for International Authors, for which the form was pretty light and they would fund trips to amounts in the region of £2500. Sadly, a few years ago the RSC decided to ditch the scheme which in my opinion was a big mistake. Other funding bodies include the Global Opportunities Fund, the Anglo-Diawa Foundation and the Royal Society, and these can be particularly useful if you want to pursue student exchanges. As you forge closer links, you may well find that overseas institutions are keen to fund the trip. At the very least, by lining up a number of seminars costs can be minimized as hosts in the Far East are keen to look after their visitors and will often pay for the hotel and will almost certainly treat you to a local feast. By far the best current method to support multiple interactions is run by the research councils, for example the EPSRC have an Overseas Travel Grant (OTG) scheme. This can provide sufficient funds to make meaningful trips and provide the opportunity to make may new useful contacts that can blossom into flourishing research collaborations. On the downside, when applying for an OTG, you still have to fill in all the usual paperwork associated with a standard EPSRC grant and they are considered (ranked against) research proposal, which in my opinion is wrong. These travel awards should be ring-fenced and only ranked against similar OTGs. All that said, a good OTG should rank highly and will have a good chance of being funded.

So back to my efforts to plant a flag in the Far East.

For a number of years now, I have been travelling out to the Far East, and along the way this has led to visiting positions at a number of leading institutions in both China (Institute of Chemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences, ICCAS, Beijing; Shanghai Institute of Organic Chemistry, SIOC, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai; Sichuan Normal University, Chengdu; Northwest University, Xi’an) and Japan (Osaka University; Akashi Institute of Technology). This has resulted in a significant strengthening of ties at all levels and has catalysed many exchanges in both directions. There have been many benefits arising from these prolonged periods in the Far East, including the opportunity to teach students (at SNU and NWU) from very different cultures which has led to new methods of delivery, the aforementioned enhanced exchange of personnel between the UK and the Far East, a boost to my research profile (ca. 130 publications with China and ca. 90 with Japan in international peer reviewed journals) and the opportunity to mentor ECRs. For the purpose of this reflection, I will focus on China, although I would emphasize that time spent in Japan has been equally rewarding. Following a number of short trips to ‘test the water’ (see introduction section above), I was offered the opportunity to spend up to 3 months in Beijing (2010) at ICCAS, a position made possible by the creation of a new scheme to attract overseas experts by the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Whilst there, I was also approached by the SIOC who were keen to set up a similar scheme to their rivals in Beijing. Indeed, in Shanghai, Prof. Guenter Helmchen (from Heidelberg University, Germany) and myself were the first two recipients of this scheme back in the summer of 2011 (see figure 1 for the award of the Professorship from Prof Kuling Ding, Director of the SIOC).

These two positions were primarily research orientated, however both gave me the opportunity to visit other institutions around China and engage with both staff and students in seminar and Q&A type settings. Much of the discussion would take place over lavish multi-course post-seminar dinners, which is a big tradition in China. On one occasion, discussions with the SIOC Deputy Director (academician Yong Tang) turned to where I might consider next for my Chinese venture. I stressed that whilst I really enjoyed my time as a Visiting Professor, the current role had its limitations, and also impacted on my life (home and work) back in the UK. Thus, if I was to consider returning to China again for a prolonged period of time, I would need my own research group/laboratory and more enhanced engagement with the various student cohorts. After a few phone calls, and following some deliberation, I chose to set up a lab at Sichuan Normal University (SNU) in Chengdu. This was also a new experience for SNU who had not previously hosted an international visitor in such a fashion. As part of the ‘deal’, two Masters level students would join the ‘Redshaw laboratory’ each year. It is worth noting that a Master’s degree in China takes 3 years, the first year involves attending taught courses as well as conducting research work in the lab, and so is a major commitment for all parties involved. At SNU and indeed in Chengdu in general, one of the major challenges is the language barrier. Very few locals can speak English, and more importantly in the Department of Chemistry & Materials, only one or two members of staff had a level of English that enabled them to engage in meaningful conversation. Therefore, to enable me to more fully interact with staff and students alike, and to be able to survive on a daily basis, I enrolled on a course in Mandarin (passport level 1) in the language department at the University of Hull. Mandarin is a very tricky language to learn given it has little in common with English and much of the language is about the use of tones (almost musical). This course involved basic reading, written and speech, and also involved partnering up with a Chinese undergraduate student. Most if not all of the class were undergraduates from the language department, and so I had to raise my game. After much determined effort and encouragement from the other students, I was able to read, write and chat at ‘survival’ Mandarin level. On returning to Chengdu, I was keen to put my newly found language skills to the test. That said, although the course had provided much useful daily Mandarin, that needed in the labs would be quite specialized and could only be ‘picked-up’ by jumping in at the deep end and learning on my feet. The supervision of the Masters students took place mostly in the research lab setting, and involved one-on-one training sessions. For safety reasons, students with some grasp of English were selected for my group. Their training was a slow process, taking place over several months, and was often a two-way process with the students teaching me the Chinese terms for the various bits of equipment/kit we used, whilst I taught them the equivalent English phrases.

As time passed, the students grew in confidence and not only were able (and happy) to fully converse in English, but mastered the use of the techniques necessary for the handling of air sensitive compounds. The weather is Chengdu tends to be on the hot side, and the culture is one of outside dining. This allowed us to conduct weekly group meetings at the likes of a BBQ or hotpot restaurant. In such circumstances, it can sometimes be beneficial to hold the meeting away from the classroom/laboratory environment, and this allows the students to relax more and creates an atmosphere whereby they feel that they can engage with and question the subject matter. It also allowed me to build up more of a rapport with the students and create an atmosphere where they were actually excited to talk about their work. Back in the lab, the Masters students were very productive, and as part of their learning process help draft manuscripts, which resulted in twelve excellent publications in the primary literature, and a book chapter.

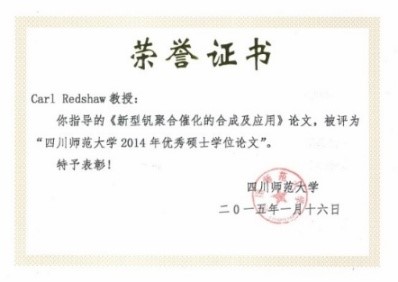

Weekly group meetings were held, mostly in English, to enable the students to prepare for their Masters presentation. All students from my group passed with flying colours, with one, Ma Jing, being awarded the prize for best Master’s thesis in Sichuan province (I was awarded a certificate for best Masters supervisor, figure 2). At the annual graduation cermony, I was the only non-Chinese Professor on stage in front of 500+ science graduates. Afterwards, we assembled for the traditional Chemistry photo (figure 3). The students graduating out of the Redshaw lab became either teachers or took up positions in industry.

After five successful years at SNU, I decided it was time for a new challenge, and via the contacts formed at ICCAS some years earlier, I was able to negotiate a similar ‘deal’ at Northwest University (NWU) in Xi’an, which is higher up the Chinese University League tables and therefore attracts more funding and possesses superior research facilities. Again, this proved to be a successful period and involved the construction of a new laboratory which I’ll chat about a bit more later. As at SNU, I delivered a lecture course, this time though on it was delivered to undergraduates on the subject of English for scientists.

In more recent times, my role has developed into more of a mentor, and as part of this role, I have run international workshops (see below), funded through mechanisms such as the Newton fund, specifically aimed at helping early career researchers (ECRs, i.e. PhD students, PDRAs, Fellows and recently appointed academics) as they start out on the sometimes-rocky pathway to a successful career. In particular, I have focused on UK researchers who wish to strengthen ties with China, Japan and latterly Russia, giving them guidance, advice and the pros and cons associated with international collaborations. Moreover, I have been ideally placed to broker ‘deals’ for other more established UK academics in order that they may either be appointed as Visiting Professors or develop/strengthen overseas collaborations.